The Rails Request, Part 2: HTTP verbs and URL paths

As we mentioned briefly in Part 1, there are a few ways the request can be sent from the browser. The most simple and obvious: you can type a URL into the address bar and hit ENTER. This sends the URL with the default HTTP verb GET.

I’ll just copy and paste into my address bar: https://www.google.com/search?q=recursion

The HTTP request is encoded and sent. These are the headers:

We can also use links (GETs), like this one

And we can use forms (most often POSTs) like this one:

And lastly, we can use JavaScript to send requests via AJAX, and these could be either GETs or POSTs.

With some of these, the mechanism is pretty explicit; with some it’s not. A tool I’ve been using lately to observe the traffic that goes through the browser is Postman. It’s a great tool that can show all the requests being sent through your browser (specifically Chrome), including random AJAX requests going on in the background. You can also use Postman to construct and send requests, specifying the HTTP verb, the path, and the query strings, great for faking out of a form submission.

The main thing to internalize here is that in each case, a URL is sent with an HTTP verb to the domain in the URL, and the server processes that URL.

So let’s start there, with the URL.

The URL has three basic parts: the domain, the path, and the query string.

The domain serves one main purpose, to ensure that the request finds its way to a server that can handle it. And while that process isn’t super simple (DNS really can be some dark magic), it’s not necessarily something you need to know to get up and running.

For Rails, the path and http verb get mapped to the specific function/method being called.

To clarify the nomenclature, a method is simply a function that belongs to a certain class. Since most things are object in Ruby, most functions are also methods. If you’ve spent time in Rails you know that Rails routing will “route” the request to a special class, called a controller and to special methods inside the controllers, called actions. So to recap, a method is a specific type of function, and an action is a special type of method.

The idea of mapping the path was a new concept for me. I developed my first website back in 2004 or so; it was a basic, purely static site where the paths were tied to the directory structure of the site. So I would throw HTML files into folders, like contact/index.html and then link to files in other folders.

But what is cool about web frameworks is that the paths can be dynamic. The old school way is still actually the default, Rails will first check to see if there is a file in the ‘public’ folder that matches the path. But if it doesn’t find a match there, it begins trying to match a route in config/routes.rb. There we specify which requests go to which actions. Remember that in order for a request to match a route, it must match on both the HTTP verb and the path.

So let’s talk for a minute about HTTP verbs. If you already have a good understanding of HTTP verbs, feel free to skip ahead.

Every URL gets sent with a verb, that is used to (1) specify some functionality and (2) indicate the intent of the request.

The default verb is GET. If you’re writing a link_to or form_for, and you don’t have a reason not to use GET, you should use a GET. GET requests are portable, you can copy and paste them. That’s behavior that you want, unless you have a reason not to.

So what are the reasons not to use GET?

1. If your request could have side effects, don’t use a GET. If the request could change the database in a substantial way, that request should not be a GET. GET requests are stored in a browser’s history. Triggering a request that has side effects by clicking the back button, for example, would be really unexpected behavior. So definitely avoid doing that.

2. If the request could contain sensitive information, don’t use a GET. For the same reason as above, you should avoid using a GET. There’s no need to have sensitive information in the browser history.

What are your alternatives to using GET. They are: POST, PUT, PATCH, and DELETE. If I’m being real honest, I mostly just use POSTs. Some people are pretty dogmatic about communicating intent with their verbs. They would describe the use cases along these lines: POST is for creating a resource, PUT is for replacing an existing resource, PATCH is for updating without replacing an existing resource. And then DELETE is for, well, deleting a resource.

But, if I recall correctly, Rails actually uses POST for everything that is not a GET and then includes a hidden field to simulate the verb being describe. Rack will have substituted that hidden field as the HTTP verb in the request object before it reaches routing.

Personally, I’m most concerned however with the functionality:

browsers will hide POSTs (and the other non-GETs) from the history and will notify you if you attempt to re-submit.

That’s the most important part.

As far Rails goes, remember that a route match requires a match on both the path and the HTTP. This serves to make routes more flexible, because it allows us to map the same path to different actions depending on the HTTP verb.

Say we have the path ‘/edit_post/:id’

We could reuse the path with different verbs for different functionality.

We might map path ‘/edit_post/84’ sent with the GET verb to the ‘edit’ action (which has no side effects) and ‘/edit_post/84’ as a POST to the ‘update’ action (which does have side effects).

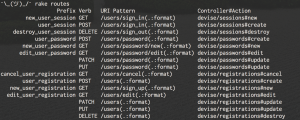

Early on, I experienced a fair number of errors, where the form I was trying to generate wasn’t specifying the URL I needed. Here rake routes was my best friend. rake routes shows you the interpreted route structure. In other words, it’s not just what you think you’re describing in config/routes.rb but how Rails is actually interpreting your routes file.

Let’s take a look at some routes generated by the authentication gem, Devise.

The first thing that confused me about these routes, were the blank prefixes. They actually refer to the prefix above them. Because we like to be DRY? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ In any case, it reinforces what we’ve talked about: a request is mapped to a function by the combination of its verb and path.

The second thing I had to learn were the default verbs for different helpers. link_tos are GETs by default, but you can get pretty funky with them if you want.

link_to "Delete", delete_profile_path(profile_id: @profile.id), method: :post

Here we’re using a post and adding to the query string.

Where link_tos are GETs by default, form helpers form_tag and form_for are POSTs by default. But again, you can override that. Rails is about convention over configuration, right? And the Rails folks assume that most form submissions will result in side effects. They’re probably right. But if the request won’t result in side effects (most common in queries), submitting a form as a GET allows the resulting URL to be portable. So I can copy and paste it to a co-worker and they’ll see the same thing I see (as long as they have the same access).

<%= form_tag( '/search', :method => :get ) do %>

<%= text_field_tag 'term' %>

<% end %>

To recap, the key thing to remember is that you, as the developer, are driving the request-response cycle. You’re writing the Ruby that gets translated into the <a> tags and the <form> tags that are transformed by the browser into HTTP requests which ultimately get sent back to you. It’s important to know what’s going on at each step in that transformation. You should know what HTML of your <form> tags look like, even though you never write that HTML. Rails doesn’t abstract away your responsibility for knowing how HTML and HTTP work; it just makes working with them a lot easier.

In the upcoming third post in the series, we will be talking about the last part of the URL: the query string, which allows to send key-value pairs in our requests. But what if we need more complex data structures than a simple key-value pair. Fortunately, Rack gives us the ability to be as complex as we want to be.